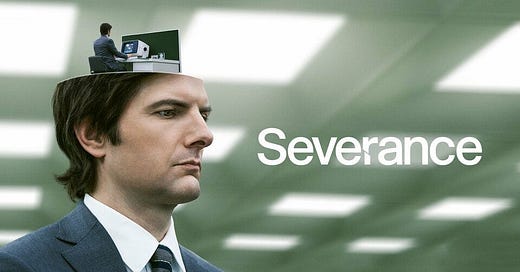

Severance has cemented itself as the new king of prestige television. You cannot go anywhere on the internet without finding communities of people theorizing about the show, news articles interviewing everyone on the cast and crew, or reviews detailing the show’s commentary on capitalism, work, and love.

Severance follows Mark (Adam Scott), a widower employed at the biotechnological company Lumon and his co-workers in Macrodata Refinement. Severance is the process of splitting one’s consciousness into an ‘innie’ and ‘outie.’ When Mark enters his job, he transitions into his innie. His innie is a consciousness that only exists to work. Mark’s innie does not have any of Mark’s memories or any recollection of how Mark exists in the outside world. Mark’s outie has no idea what his innie does at work. Mark works on the severed floor, meaning all employees (except for those in management) have also gone through severance. Mark works in Macrodata Refinement with Dylan (Zach Cherry), Helly (Britt Lower), and Irving (John Turturro). Their only job is to sort numbers into files on a computer by how those numbers make them feel. As the series progresses the four explore the severance floor outside their office and attempt to map the maze of white hallways that keep them locked away, hoping they will learn what work they are actually doing, and find a way to escape the floor with their consciousness intact.

The plot of Severance is as dense and as labyrinthine as the halls of Lumon. It’s a retelling of Orpheus and Eurydice, it’s a meditation of consciousness and grief. It’s a critique of capitalism and the politics and religion that intertwine with oligarchy. It’s also a story about love. Because this is a queer blog, I will only discuss Irving’s romantic storyline with Burt (Christopher Walken). However, the show is much bigger than one queer storyline. You should also watch it for the performances of queer actors Tramell Tillman as Milchick, Lumon middle management, and Jen Tullock as Mark’s sister, Devon.

In the first season of Severance, Irving is the most dedicated employee on the served floor. He doesn’t question his superiors and he reads the employee handbook like it is the Bible — and it is literally written like the Bible. He meets Burt, and the two connect over a painting of Kier that hangs in a waiting room. Irving becomes more rebellious as he sneaks off to see Burt and map the winding halls of the severed floor to reach him. Maps are strictly prohibited in their handbook. Burt breaks the rules and shows Irving the secret room in the Optics and Design department where the employees actually work. Burt is forced to retire because of this incident. Retirement is essentially death, since the innies consciousness only exists inside of Lumon.

At the end of the season, Mark, Helly, and Irving are woken up as their innies in the real world. They each need to find a trustworthy person to tell what the severed floor of Lumon is like. Irving wakes up alone in his outie’s apartment. There is no one he can tell. He goes through a trunk of his outie’s stuff, and finds detailed information on all of Lumon’s severed employees, including information about Burt. He runs to Burt’s house and sees Burt — well Burt’s outie — with another man. He continues his mission and pounds on the door.

After the events of Season One, Irving’s outie is invited over to Burt’s home for dinner. Irving learns that Burt and his partner Fields (John Noble), have worked with Lumon before the severance procedure existed. Burt was one of the first severed employees. Fields reveals that Burt was severed so a part of his soul could be purified. Outie Burt views innie Burt’s retirement as death. Innie Burt has gone to heaven. Fields wanted to be with his husband in heaven. He is upset to learn that the spirit that was supposed to join him in heaven fell in love with someone else. The purity of that being has been tainted by Irving’s innie.

No character in Severance is overtly homophobic. No one judges Irving for being gay, they judge him for having a workplace relationship. The force keeping him from romance is work, is God. Irving and Burt’s relationship is about religious conformity, purity, and the blurry line between love and sin. It is a metaphor for queer people’s relationship with the church and with Heaven. Their story is literally queer and metaphorically queer.

Severance’s speculative elements allow the viewer to be unsettled by the religious beliefs espoused by Fields. If Burt had a wife, if the religion was Christianity and not a Lumon brand version of it, the audience would most likely see it as, “Homosexuality is a sin and Burt needs to be purged of that sin.” They wouldn’t have to consider what purity and sin mean to this corporate religion. Severance wants you to think about purity and love. It doesn’t want the audience to conclude “Well it’s gay, so of course they believe it’s impure.” Instead, Burt’s consciousness is split in two pieces for religious salvation, and that religion is this strange corporate mystery the viewers have not unraveled yet. Instead of being angry the audience is disturbed and horrified. Something is wrong with Lumon and its religion. It’s insidious. We don’t take the religious belief of sin and purity for granted; we see it through a different lens.

Irving and Burt’s love is pure. Their innies are giddy about holding each other’s hands. They just want to spend time with each other and talk about art. They are sweet. Their outies are the same. Their conversations are serious but the feelings they have for each other are sweet. They long for a simple love. Irving admits to Burt that he never had the chance to have a relationship. His innie experienced an innocent love he’s never even felt, that he barred himself from feeling. Irving and Burt’s love is not a corrupting thing in either consciousness. It is an expression for a longing of something simple — something unmuddied by the weight of the world. By the complications of life. Burt found purity, but he did not find it through his religious beliefs. He found it through love.

In Severance the innies experience what the outies desire, because the innies lives are uncomplicated. The things their outies have to worry about are not supposed to exist on the severed floor. Severance is a show about love, and its thesis is that feeling love, experiencing it is sweet. The world, religion, work, make love difficult. Love is simple; love is pure.

About the Author

Anne Gregg is a poet and writer from Northwest Indiana. She is an English Writing major at DePauw University and is the editor-in-chief of her campus’s literary magazine, A Midwestern Review. She is a Media Fellow at her university and loves dissecting how LGBTQ+ people are portrayed in film and tv.